Rewiring For Relevance.

Exploring how we adapt to AI and reshape work.

Every evolution has made us fearful. Every revolution has made us hopeful. Every disruption should make us mindful.

So where does Artificial Intelligence sit along that spectrum?

The technology itself isn’t new. Today’s surge in announcements and investments is the result of decades of research and development. In that sense, this could be seen as a logical evolution.

But the current intensity — the spotlight, the scramble, the scale — feels like a disruption. Whether it turns out to be a revolution is something only time will tell.

“AI Revolution”? Beware of social media-friendly headlines. We risk confusing noise for signal.

More importantly, we will shape AI as much as it shapes us. That’s why this moment — the thinking window that I wrote about here — matters.

For now, I observe with circumspection an unquenched thirst for global dominance. An impervious imperative to turn large language models into large profit machines.

But I also see an opening. An opportunity to redefine our roles in society. I want to begin exploring whether — and how — we’ll adapt to a new kind of work environment. (Assuming our world remains work-centric — which is, frankly, a questionable assumption.)

This is a narrow lens, but a useful one. For those looking to zoom out, I recommend essays by thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari (“21 Lessons for the 21st Century”), Carl Benedikt Frey (“The Technology Trap”), or the latest reports by the McKinsey Global Institute and the OECD on the future of work.

Let’s dive in.

When it comes to human adaptation, the past may not predict the future — but it helps.

Each significant societal transformation changed where we work, when we work, and how we work. The economics of work evolved.

In the Agrarian Age, the main unit of value was land.

In the Industrial Age, it was labor.

In the Digital Age, it became intelligence.

None of these shifts were frictionless. There were objections. Luddite protests, coal miner strikes, resistance to automation.

But each shift brought relief from previous constraints:

The Industrial Era introduced advanced agricultural machines, freeing farmers from geographical and seasonal limitations.

The Digital Era enabled smart manufacturing, compressing time and increasing productivity per hour worked.

So what’s next?

Will the post-digital era help us address today’s main constraint in developed economies — attention? I don’t think anyone has a definitive answer.

But one thing is clear: our brains have adapted — when they were forced to.

Let’s look at how we’ve used them:

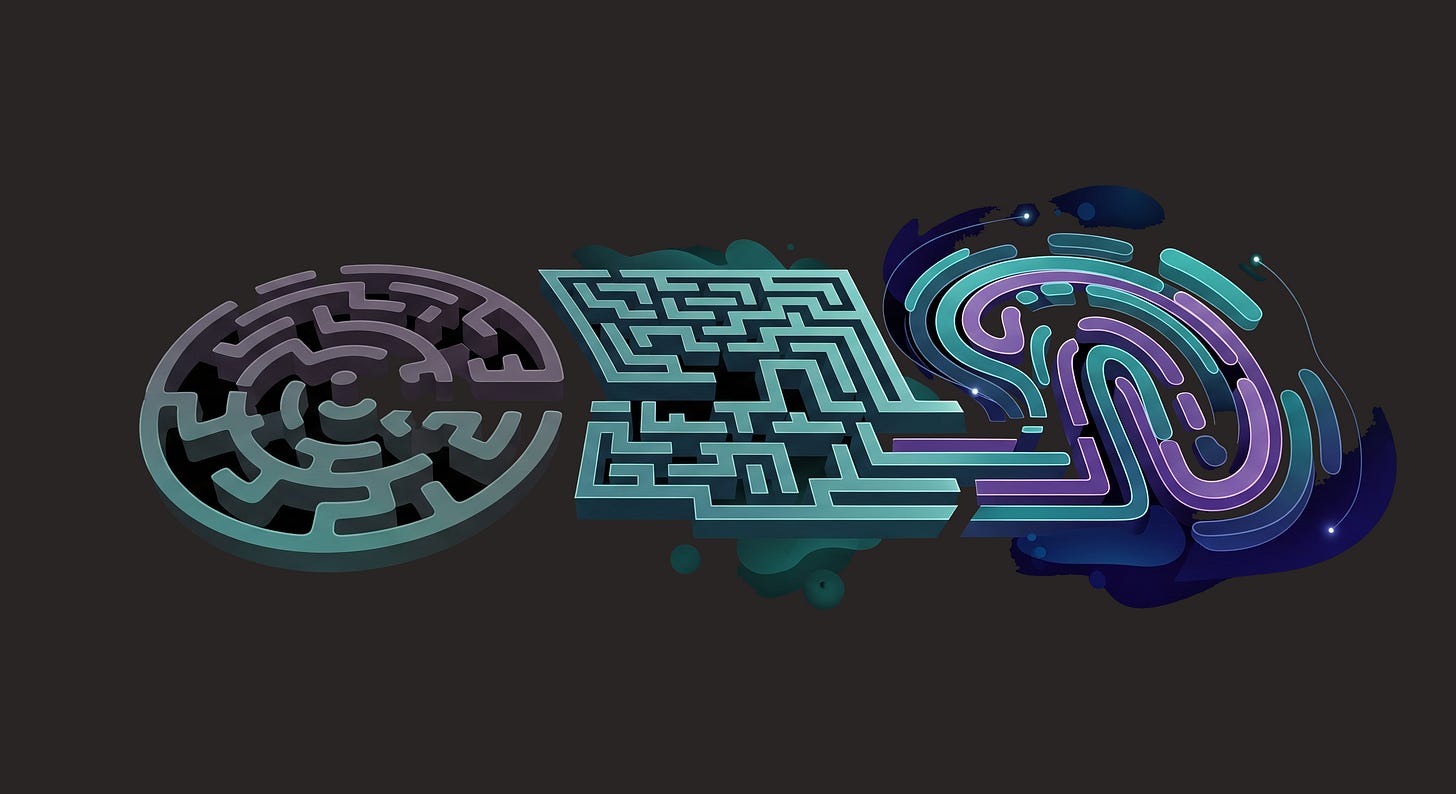

In the Agrarian Age, we memorised.

In the Industrial Age, we serialised.

In the Digital Age, we synthesised.

On the whole, our cognitive capacity hasn’t declined. It has rewired.

One longitudinal study published in Nature (2009) found that working memory and fluid intelligence have improved steadily over time, despite fears of decline.

So now that machines are synthesising dots at breakneck speed — what do we do?

There’s white space for:

Determining the best connections between dots — that’s critical thinking, propelled by AI. Think: strategic advisors who must validate AI-generated options before they go to market.

Imagining these dots from different angles — that’s collaboration, fluidified by AI. Think: product managers working across diverse teams, cultures, and AI tools to align goals.

Creating entirely new dots — that’s creativity, fostered by AI. Think: artists, designers, or educators who use generative models to unlock new forms of storytelling or learning.

On AI, there are more schools of thought than I can count. But if history is any guide, we are not witnessing the arrival of a replacement — we are welcoming a new partner. A powerful one, yes. But a partner nonetheless.

So are we entering a Relevance Era — where humans redefine what only they can do?

Or an Irrelevance Era — where we slowly sideline ourselves?

As always, the answer will depend less on technology — and more on us.